Campaign > Persian Campaign > Battle of the Granicus

Battle of the Granicus

Battle of the Granicus

Part of the Persian Campaign

Le Passage du Granique - Charles Le Brun (1665)

Date: May, 334 BC

Location: Granicus River, Hellespontine Phrygia

Coordinates: 40°13′41″N 27°14′32″E

Aftermath: Macedonian victory

Territorial Changes: Alexander gains half of Asia Minor

Next Battle: Siege of Miletus

Previous Battle: Balkan Campaign

Background

The Battle of the Granicus was the first major engagement between Alexander III the Great commanding his army of Macedonians, Greeks, and Thracians facing off with the vast armies of the Achaemenid Empire under the high command of Darius III. During this engagement the Persian forces would be lead by general Memnon would be defeated by the combined assault of Alexander.

Before the battle most of the Persians saw Alexander as no threat to them at all. Alexander had come to Asia with no supplies, hardly any money and intended to forage and scavenge what the army needed as he conquered along the way. Memnon had brilliant foresight and thought the Persians should retreat slowly and practice a policy of scorched earth so that Alexander would be forced to turn back before he got started.

In essence they believed by removing all the supplies and valuables along the way they would discourage the Macedonian invasion of their empire. Memnon's strategy would have probably worked as hungry armies hardly fight effectively and they would have either gone home or been easily defeated if deprived of all supplies. But in the end Memnon was ordered to make a stand at the Granicus River, the conflict serving as a public relations opportunity for both sides.

Alexander would win a decisive victory at the Battle of Granicus that would allow him to literally walk through Anatolia unimpeded, claiming all the territory along the way. It was the victory at this first battle that would give him the momentum to ultimately claim the rest of the Persian Empire.

The Battle

Alexander saw joy in the coming as a battleground to test his merits against the massive Persian Empire. Following Alexander's orders the army approached the bank of the shore and went into battle formation. The Macedonian phalanx acquired from his father was going to serve Alexander very well in the upcoming engagements.

Want to learn more about how Alexander the Great's military functioned and the strategy behind why it was so successful? Click here to learn about Alexander the Great's military.

Alexanders army arranged and organized on one side of the river while the Persians had amassed in huge numbers on the other side of the river. Some historians say there was one hundred thousand Persians, others say 200,000 and even others say 600,000 Persians greeted Alexander at this river. Regardless of the number they were vastly superior to Alexander's military which numbered about 40,000 so the young Alexander was in for a tough fight.

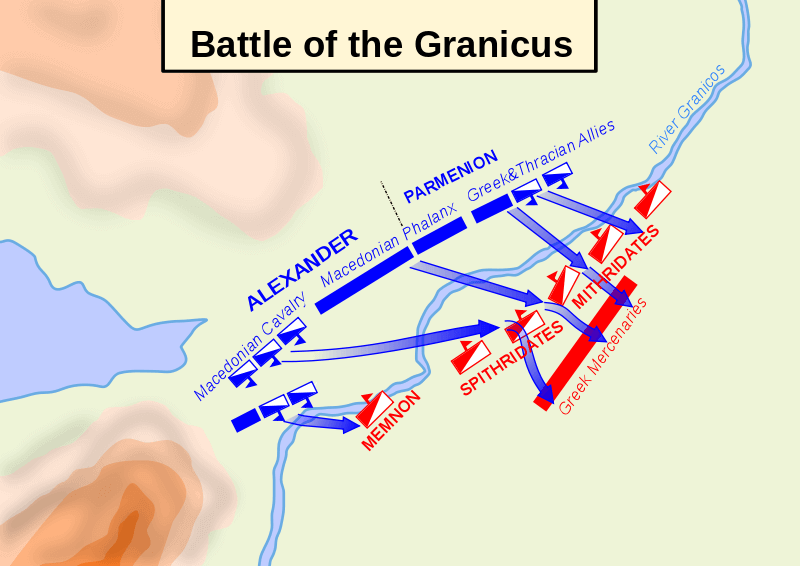

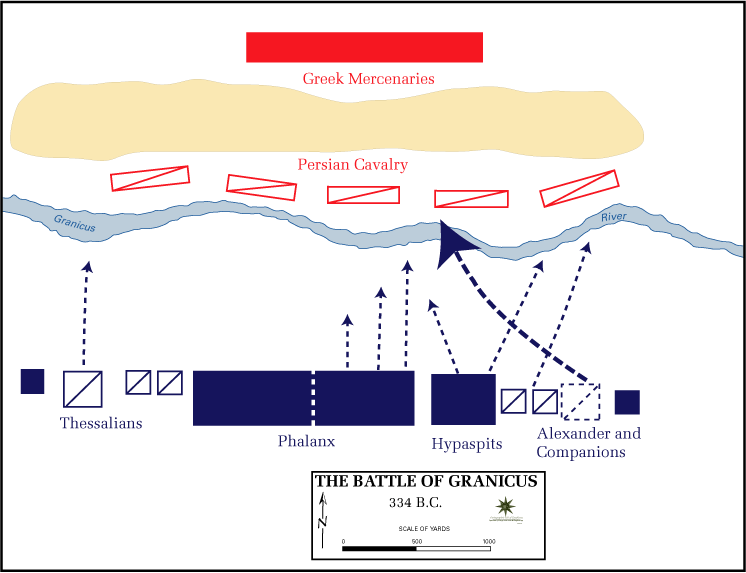

Battle of the Granicus Formations

The Persian cavalry moved into formation right along the river banks and was ready to assault the invading Macedonian army as soon as they emerged from the shallow water. Personally leading his army, Alexander and his troops crossed the river and moved through the water. A horrible battle ensued between the forces but Alexander was able to push through the forces and establish a position on the opposite shore. The Greeks reformed and the Persians scattered as they experienced their first major defeat at the hands of Alexander.

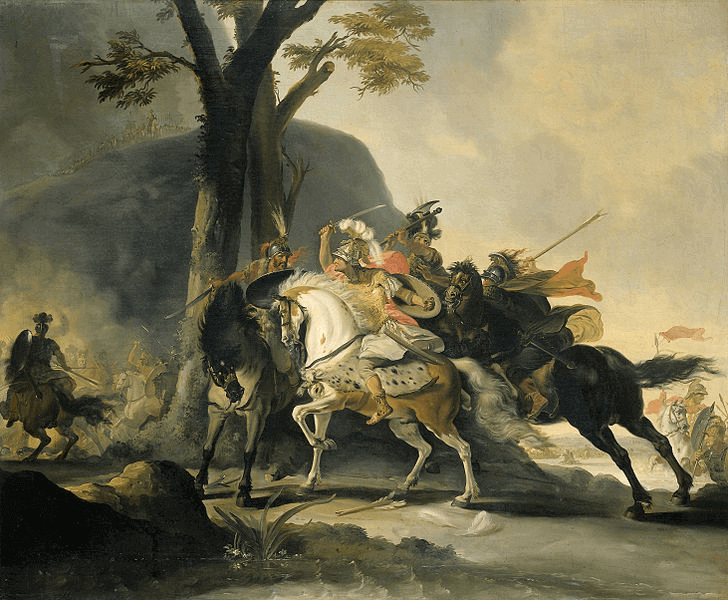

During this engagement Alexander was noted to have taken a very active role and was apparently easily recognized on the battlefield through the white plume he wore in his helmet. He was exposed to some of the most danger and according to ancient sources one time during an engagement with a Persian cavalry he was able to duck just quickly enough so that the plume and part of his helmet was taken off. Alexander then took his sword and plunged it through the body of the Persian soldier. A second Persian cavalry was also moving in for the kill on Alexander when a third combatant, one of Alexanders friends managed to strike him with such a force as to cut his arm off before the Persian could swing his sword.

Battle of the Granicus - US Military Academy Ancient Warfare Atlas Index

Who knows if these stories are true or not, but there is no reason to doubt their authenticity as this was the nature of Alexander the Great's Campaign. It is also well known that the poets of and historians of the time were known to ascribe the deeds of other soldiers to that of great generals to make their accomplishments seem larger than life. There are no available Persian accounts of this event either. What is known is that Alexander emerged victorious from that day and he was content to let their forces scatter. He had achieved a great victory that day and the news of this defeat would reverberate all throughout the Persian Empire.

Alexander in Battle at the Granicus - Cornelis Troost (1737)

After the victory Alexander sent back to Greece an account of the engagement along with 300 suits of Persian armor taken from the battlefield. They were hung up in the Parthenon in Athens, and also rumored to have been sent to Sparta as well with the note saying this was won with the help of all the people of Greece besides the Spartans for their lack of participation in his army.

Alexander and his army then set up camp on the opposite side of the Granicus and begun to take care of the wounded. According to the histories Alexander went one by one to each of the men and listened to their stories of how they became wounded in battle. To be able to tell their story to their general and king and have him actually listen greatly inspired the men and boosted morale within the entire army. This closeness that Alexander had with his soldiers would bond their loyalty for the decade long campaign to come.

| Combatants | |

|---|---|

| Achaemenid Empire | |

| League of Corinth | Asia Minor Satrapies |

| Commanders | |

| Arsames | |

| Hepaestion | |

| Parmenion | Rheomithres |

| Cleitus the Black | Niphates † |

| Calas | Petenes † |

| Hegelochus | Spithridates † |

| Ptolemy | Mithrobuzanes † |

| Arbupales † | |

| Mithridates † | |

| Pharnaces † | |

| Omares † | |

| Arsites † | |

| Rhoesaces † | |

| Memnon | |

| Military Forces | |

| 32,000 infantry (12,000 Macedonians, 7,000 other Greeks, 5,000 mercenaries, 7,000 Odrysians, Triballians and Illyrians, and 1,000 archers) | 10,000-20,000 Cavalry |

| 5,100 cavalry (1,800 Macedonians, 1,800 Thessalians, 600 other Greeks, and 900 Thracians and Paeonians) | 5,000-20,000 Greek Hoplite Mercenaries |

| Total: 37,100 | Total: 20,000-40,000 |

| Casualties | |

| 300-400 Killed | 3,000 infantry killed |

| 1,150–1,380 to 3,500–4,200 wounded | 1,000 cavalry killed |

| 1,150–1,380 to 3,500–4,200 wounded | 2,000 captured |

Aftermath

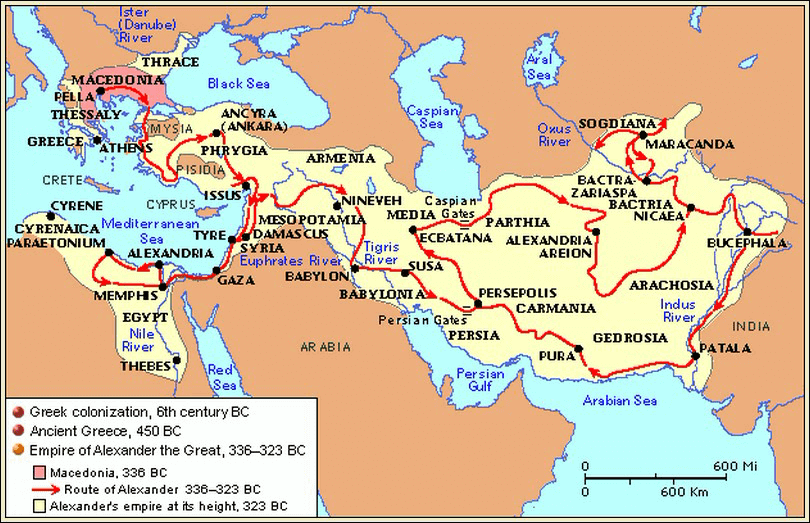

After recouping the and planning Alexander decided to move his army south and east along the shore of the Aegean Sea. After the Battle of the Granicus many of the countries he encountered along the way surrendered without a fight. He was actually viewed more as a liberator since many of these territories in Anatolia were actually Greek to begin with.

Along the way he most likely gained extra soldiers from each of the territories that submitted to him. Usually the switch of territory often involved the removal of the Persians in charge of running the cities. He made sure his soldiers never killed anyone they did not need to and often kept the same systems of governance in place.

He never took any personal property throughout Anatolia, only installing his people within the government citadels and confiscating other government property. He generally continued the same taxation and legal systems that were in place before. As Alexander marched through Anatolia more and more cities peacefully accepted his rule.

Alexander's Military Campaign - Alexander the Great (1848)

By winning a decisive victory at Granicus he was able to do exactly what he planned and win a symbolic victory over the Persians. Even if he had taken many casualties in the end it was worth it because throughout Anatolia he was probably able to win many of the battles without even fighting them. This method of public relations in regards to victory was what allowed Alexander to truly have his reputation precede him. In some places before Alexander arrived there would actually be small civil wars that would break out between Pro-Greek and Pro-Persian parties.

At the city of Ephesus the Pro-Greek party had gained the upper hand and was going to massacre the Pro-Persians. Alexander intervened in order to protect the Pro-Persians and forbade and massacres during the transfer of power. This respect for the eastern cultures would ultimately be what would move them to accept him as King of Asia when he conquered the Achaemenid Empire over the next several years.

The war for the Achaemenid Empire was far from over however, and Alexander was soon to meet Darius III himself at his next engagement at the Battle of Issus.

It was the custom in those days for the mass of the common soldiers to be greatly influenced by what they called omens, that is, signs and tokens which they observed in the flight or the actions of birds, and other similar appearances. In one case, the fleet, which had come along the sea, accompanying the march of the army on land, was pent up in a harbor by a stronger Persian fleet outside. One of the vessels of the Macedonian fleet was aground. An eagle lighted upon the mast, and stood perched there for a long time, looking toward the sea. Parmenio said that, as the eagle looked toward the sea, it indicated that victory lay in that quarter, and he recommended that they should arm their ships and push boldly out to attack the Persians.

But Alexander maintained that, as the eagle alighted on a ship which was aground, it indicated that they were to look for their success on the shore. The omens could thus almost always be interpreted any way, and sagacious generals only sought in them the means of confirming the courage and confidence of their soldiers, in respect to the plans which they adopted under the influence of other considerations altogether. Alexander knew very well that he was not a sailor, and had no desire to embark in contests from which, however they might end, he would himself personally obtain no glory.

Sources

Warfare Links

- Agrianians

- Alexanders Military Structure

- Alexanders Military Tactics

- Alexanders Military Units

- Alexanders Military

- Antigonid Army

- Antigonid Military

- Antigonid Navy

- Argyraspides

- Baggage Train

- Bematist

- Companion Cavalry

- Greco Bactrian Military

- Hellenistic Armies

- Hellenistic Armor

- Hellenistic Battles

- Hellenistic Cavalary

- Hellenistic Chariots

- Hellenistic Diplomacy

- Hellenistic Fortifications

- Hellenistic Infantry

- Hellenistic Militaries

- Hellenistic Military Architecture

- Hellenistic Military Engineers

- Hellenistic Naval Battles

- Hellenistic Naval Warfare

- Hellenistic Navies

- Hellenistic Shields

- Hellenistic Siege Engines

- Hellenistic Siege Warfare

- Hellenistic Siege Weapons

- Hellenistic Spears

- Hellenistic Treaties

- Hellenistic Warships

- Hellenistic Weapons

- Hellensitic Helmets

- Hetairoi

- Hypaspists

- Hyrcanian Cavalry

- Macedonian Army

- Macedonian Phalanx

- Machimoi

- Metalleutes

- Paphlagonian Horsemen

- Persian Immortals

- Pezhetairos

- Phrourarchs

- Prodromoi

- Ptolemaic Army

- Ptolemaic Military

- Ptolemaic Navy

- Saka Mounted Archers

- Sarissa

- Sarissophoroi

- Seleucid Army

- Seleucid Battles

- Somatophylakes

- Sphendonetai

- Strategos

- Toxotai

- War Elephants